A low-cost housing proposal for Cambodian families, won in an international competition run by Building Trust International and Habitat for Humanity Cambodia. The proposal is premised on the vernacular Cambodian dwelling of a single family room, incorporating cooking and sanitary areas by way of a bridge over a small courtyard garden.

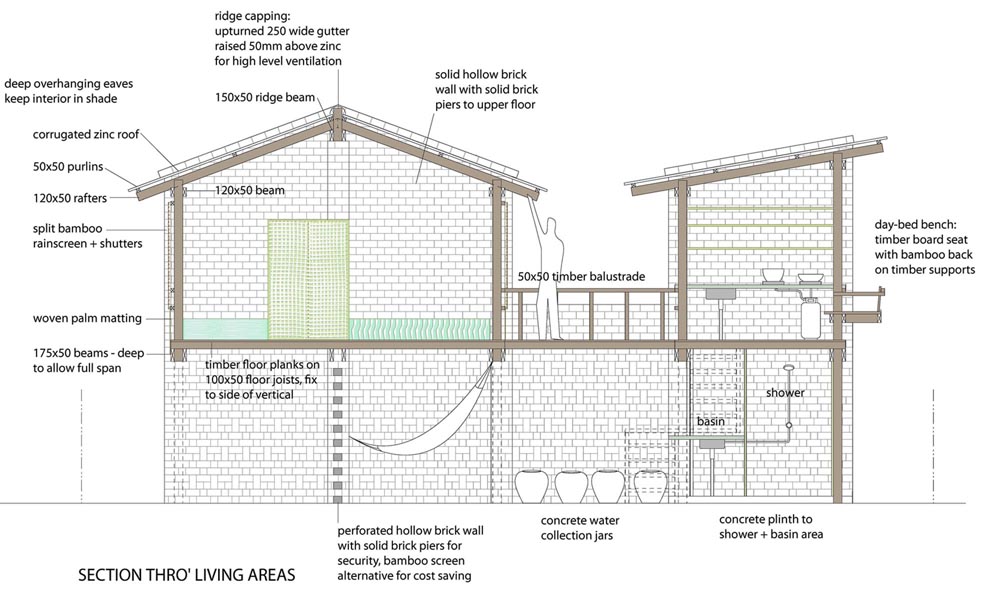

The Courtyard House aims to combine elements of the traditional Cambodian dwelling with a number of extraneous elements that make the idea of a comfortable, attractive, healthy and sustainable house for a medium-sized family possible in the given circumstances. Spatially the most important being the inner courtyard that physically & visually connects the ground and raised living areas.

The idea of a house built on stilts is deeply ingrained in Khmer thinking and still the preferred option of the vast majority of inhabitants of the country. The size of the plot, however, reflects the constraints brought about by a rapidly growing population, in particular in the central provinces, which calls for higher density and new approaches. In reality, this often leads to the abandonment of Cambodian forms of dwelling, in particular in favour of Vietnamese solutions that are imported with a rampant building industry and high levels of expertise and efficiency.

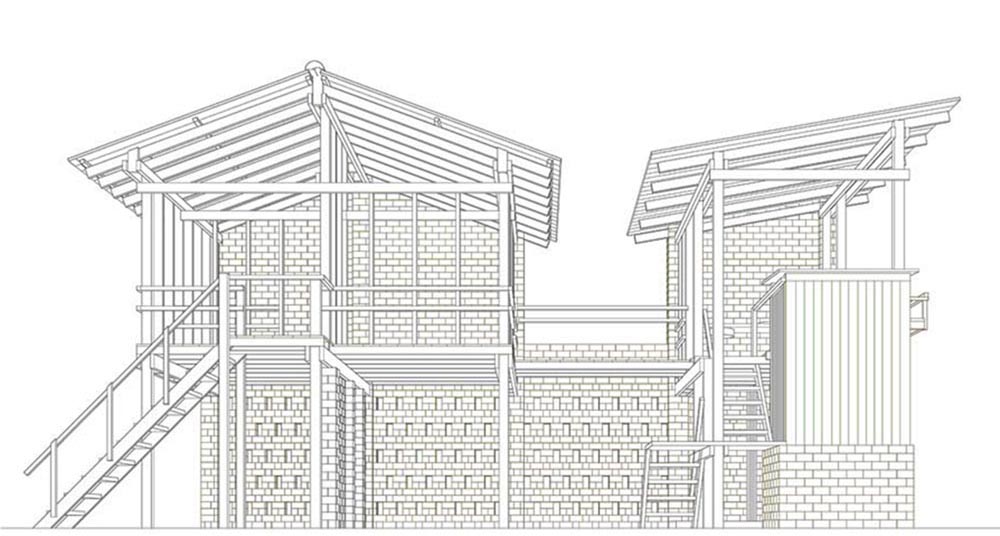

On the other hand, the long history in dealing with high-density living in Vietnam and Southern China has also allowed us in this case to find a solution that both respects the Cambodian roots and benefits from those neighbouring cultures with their preference for courtyard layouts. The composition of the house shows a raised dwelling house at the front that is connected with a two-storey utility area at the back, thus leaving a space in the middle of the plot which offers both a degree of openness and spatial separation from neighbours’ properties.

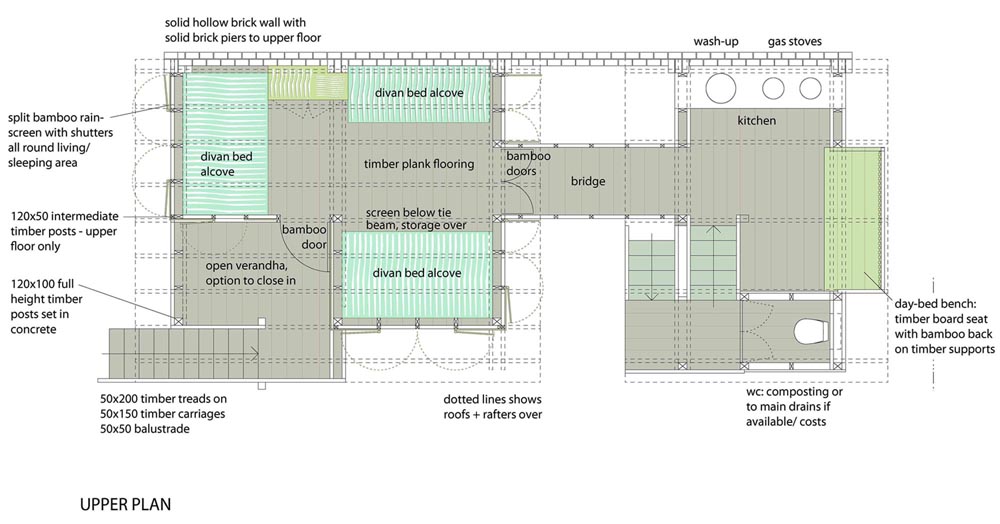

While both spatial constraints and respect for traditional family life make an individual bedroom-based plan for the living area inappropriate, this part of the house, usually a single family room, is designed in the form of alcoves which afford a modicum of privacy if required (for example by screening off a bedroom area for adolescent daughters, as is customary).

Due to the use of light, flexible cladding, the open deck area at the front of the house could be walled in so as to provide additional living space for extra family members. Additional storage can be provided by slinging planks over the tie beams.

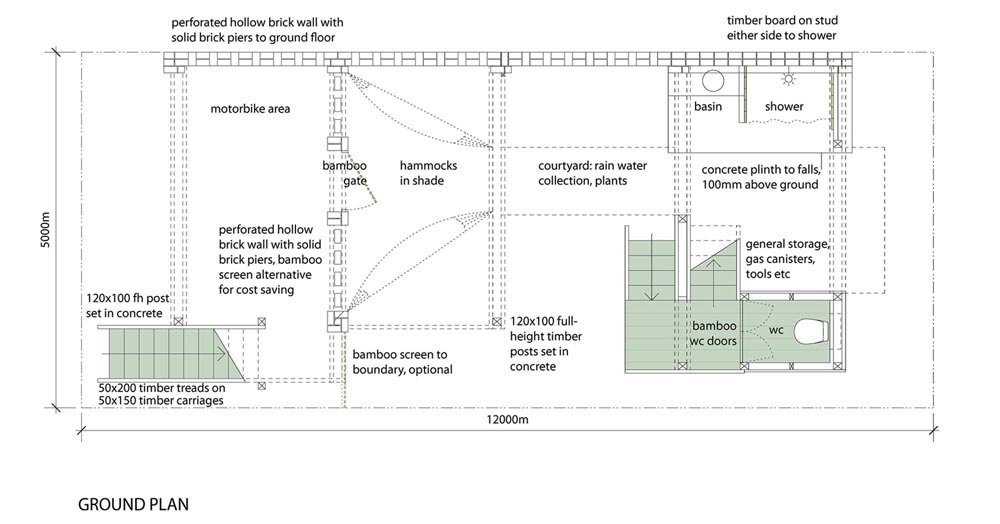

While the “utilities” in Cambodian houses (cooking, washing, toilet) are often marginalised if not absent, they receive here a somewhat higher status by being incorporated into the overall composition of the house, spatially organised and connected with the living area by a bridge. This reflects the increasing significance in Cambodian life of aspects like cleanliness, sanitation and healthier living. The kitchen is visually connected to the house, and with a daybed also somewhere to rest in. The toilet box is installed at half-flight on a raised brick plinth, the height can be varied to suit local flood levels, here shown at 1.2m above ground. Depending on the location and the budget either a mains sewer toiler or a composting type can be installed.

An equally emerging issue, i.e. security, is provided by the introduction of a (perforated) brick wall at ground level that allows the closing of most of the ground floor area towards the street front, with bamboo screens to complete the enclosure, creating an enclosed rear courtyard-garden.

The choice of materials also reflects a dual approach, with prominence given to traditional solutions such as timber, (split and whole) bamboo and palm leaf matting which can be sourced locally and through which local builders and their longstanding construction techniques can be supported. At the same time, reasons of cost, practicality and durability suggest the use of some modern materials, e.g. corrugated zinc for roofing (preferable to flat zinc sheets for climatic reasons), brick and concrete.

Cambodia’s climate and fauna, in particular the heavy monsoon rains, make the stilt-type of construction highly preferable, as it protects the family’s possessions from flooding while keeping dangerous animals away from the inhabitants (this is also taken into consideration in the raising of the toilet block). Apart from following this eminently sensible typology, the construction of the house is particularly devoted to the use of natural ventilation, by giving the inhabitants a wide choice of openings in the living area so as to allow air movement to develop in the frequently stagnant humidity of Cambodia. We have proposed that the ridge cap is raised up off the roof to allow warmer air to simply rise out through the ridge. As is traditional, the eaves overhang deeply to shade the interior from the powerful direct sunlight.

One of the most prominent features of the Courtyard House is the use of the brick wall that closes the composition towards one of the neighbouring plots. At ground floor it is proposed that the wall is perforated to shade but also to allow share ambient light, the upper floor would be solid. This construction element was chosen not only for its fire-preventing capabilities but also because it allows the configuration of the house as part of a larger scheme. This can be either in semi-detached form or as terraces. In the latter scenario, the houses would find themselves bordered by brick walls on either side – in a manner not unlike that common in Southern China – but at the same time retaining a connection with the open space through the courtyard.

The courtyard is a vital part of the configuration of the house, providing shaded areas to laze about in, but also for planting & rainwater collection, keeping chickens. Visually it forms a layering between the living area and the utilities, allowing in light and air & creating a sense of depth and expansion - alleviating the modest dimensions of the house.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|